Contents

There are two reasons to walk from Tambomachay to Cusco.

1] It’s a nice day out on an easy walk where you get to see a good number of ruins under your own power and timing. You visit the popular bus tour sites, as well as others that have no roads.

2] You get to experience maybe just a hint of Inca thinking and belief by walking along their sacred paths that connect their important and special places. But to understand the second reason requires a bit of knowledge. I’ll try to make it brief with an quick overview of some Inca concepts.

Helpful Inca Concepts

First there’s Cusco. Cusco was literally the center of the Inca world. The Inca called their empire the Tawantinsuyu, meaning the four quarters joined together. The empire spanned from Ecuador to Chile and from the Pacific coast to the Amazon. And the four regions all met in the city of Cusco, in the central square, what’s now the Plaza De Armas — the very center and axis of the known world.

Next are wak’a, or huaca. These are often called Inca shrines, and indeed they are places that they deemed holy or special. But wak’a are more than a manmade structure. Wak’a can be an interesting rock, a spring, a mountain, a good view — any thing out of the ordinary could be considered by the Inca as a ‘sacred thing.’ And this includes both natural and manmade places.

Finally there is the ceque. Ceques are abstract lines radiating out from the central square in Cusco. Each quarter of the Tawantinsuyu had a set number of ceques (some 9, some 14) that all started in Cusco and went outward. Along these lines lie wak’a, so the ceque are also paths that connect sacred things. And thus the ceque could be experienced as a ritual procession. The Inca would journey along the ceques and perform rituals.

Of the 41 ceques recorded as coming from Cusco, this walk goes along parts of two of them, passing through the landscape and stopping at places that could have been wak’as. We performed no rituals, other than the usual tourist ritual of photography. And we walked to Cusco, rather than from it, simply because it is downhill. (There’s a map at the bottom of the post if you’d like to know our exact path.)

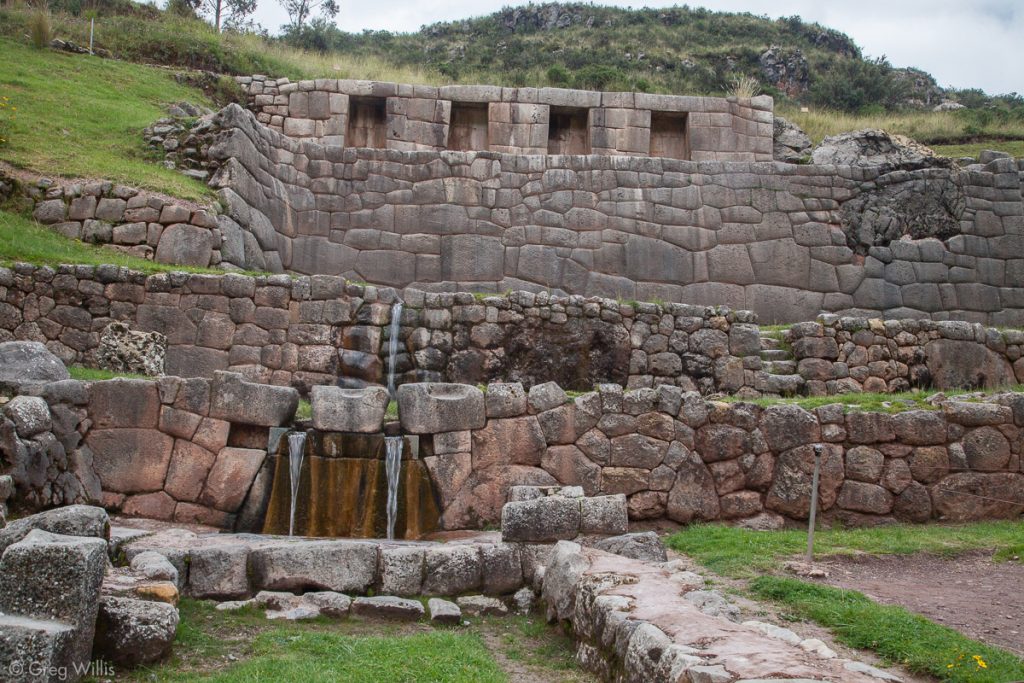

Tambomachay

We caught a cab in Cusco to our farthest point, Tambomachay. Tambomachay means ‘guest house cave’ in Quechua, and up the side of the valley facing the ruins you can see a triangular bit of darkness that is a cave, the wak’a that’s at the end of one of our ceques.

The ruins are nestled up in a side valley on the road to Pisac. And there’s not that much to it: a couple of doorways, a few niches, a water feature, and a platform on the opposite side of the valley to view it all. But I think its small bearing makes it an intimate place. You may have to wait for time between the waves of bus tourists, but if you do you’ll find the the gentle sounds of the splashing fountains filling the open space between the hill and the mountains.

And the fountains of Tambomachay are a beautiful example of the Inca’s skill with water. Most ruins have an element of water to them, and the Inca were adept at moving water through their wak’as using channels and waterfall fountains.

Pucapucara

From the Tambomachay parking lot Pucapucara is just a five minute walk down the road. The Quechua name means ‘red fortress’ but no one really knows what its original purpose or its original name was. It has a dramatic vantage point to view down the valley, but whether its importance was aesthetic or military we can’t know.

Pucapucara is round, and that’s unusual. The Inca were rather rectilinear with their constructions. The main gate has a double-jamb, which indicates high status — so this wan’t a place for regular folks. You get a good demonstration of the masonry interacting with existing outcrops. Chicha, a fermented corn beer, figures in the rituals of the Inca — probably not dissimilar from “pouring one out” that we have today. One section has a large limestone outcrop carved so that chicha would cascade down over its sculptured surface. We did not try this out. But those views — definitely the main reason to visit.

Qocha

This being a limestone (or karst) landscape, you’re gonna get sinkholes. We walked down from Pucapucara and off the road on a path. It took a bit of wandering but we eventually and found Incan qochas. The Inca enlarged the natural sinkholes to form qocha, or reservoirs. We found a couple of these with a channel connecting them. They lie just to the east of a larger lake called Huayllarcocha, so this was probably all a part of an irrigated landscape engineered & built by the Inca.

Chuspiyoq

We continued along the path which led us into a small valley. We approached a large 2-storey-house-sized limestone outcrop and noticed that it too had been carved and modified. This was Chuspiyoq , which was only marked as ‘Inca shrine’ on my map. The Inca had constructed a small (4″) channel running around one side of the outcrop and into a complex series of small pools. Another channel came from the other side on the valley bottom and joined up with it in front of a large carved platform-sized niche. More niches completed the scene along with further carvings on the outcrop. This is a great wak’a with no ticket required.

We continued along the floor of the valley, and we could tell that this was a special place along the ceque for the Inca. On either side stood many caves & outcrops with platforms. One of the larger unnamed wak’as had a small cave with an offering of fresh coca leaves still on the altar and an outside carving of a bowl.

Laqo

Laqo, also known as Templo de la Luna, is another wak’a, an outcrop much larger than the previous ones — about the size of a three-story office building. The Laqo carvings has something we hadn’t seen before: recognizable animal forms. We saw the condors, pumas, and snakes in addition to the more common flattened platforms on its top. It also has has caves and adjoining buildings at its base. And the whole thing has a 2-3 foot fissure in it, diving the outcrop into two. Many wak’a have splits or fissures, so this trait must have been important to the Inca.

Kusilluchayok

After Laqo we walked an Inca road to Kusilluchayok, or Templo de los Monos. The road was wide and regal, bound on both sides by low walls and having occasional niches and even a water feature.

This temple was smaller and seemed to be a jumble of car-sized rocks. The site has many levels — from carved outcrops to multiple caves. In the center is another rock carved with pumas and so that chicha would flow down its manmade channels.

Qochapata

From Kusilluchayok we walked around a hill, into a residential area, and eventually got to the main road the taxi took to Tambomachay. Across the road is a stand of eucalyptus trees and a ruin without much information. It had a limestone outcrop with a few buildings in front. From what I read it seems to be related to Qenqo, the site across the road

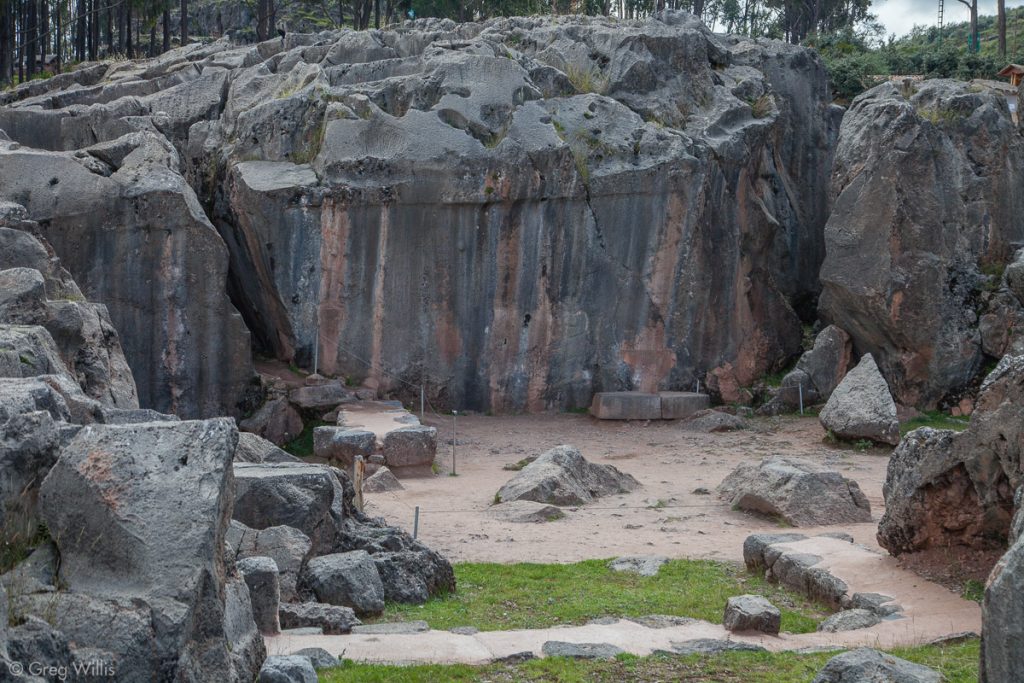

Qenqo

So, if you’re gonna hit just one, make it Qenqo. It’s quite impressive — on the bus tours for a reason. It has everything: carved surface, chicha channels, cave, intiwatana, mummy niches, corridors, ledges, altars, thrones. A veritable greatest hits of Inca wak’a modification. We visited during the tourist lunch lull, so we had the place to ourselves. The amount of carving alone is enough to show that this was a very important wak’a, probably the most important one on the walk. And the number of enclosed spaces give it an intimate feel that other lacked.

Qenqo Chica

Qenqo Chica, little Qenqo, is just down the hill from Qenqo. Probably related to both Qenqo and Qochapata as a grand ceremonial complex, the interest at Qenqo Chica is in the walls. Much like Sacsaywaman just to the west, the walls at Qenqo Chica contain large automobile-sized stones that the Inca fitted into the masonry below them and then they lowered them into place.

Qenqo Chica sits in a pretty park with trees and grass — perfect for a picnic. We continued down an obscure path and crossed the Av. Circunvalación into the city of Cusco.

For the Inca journeying on the ceque, the city held more wak’a and the ceque did not end until arriving at the main square. For us, however, most of the wak’a in Cusco were destroyed after the Spanish conquest, so it’s difficult to to follow the line in an urban area so changed. But mostly, it was lunch time. So we hungrily followed our new path to find lunch.

- Date: Mon 10 Apr 2017

- Start Time: 07:45

- End Time: 12:15

- Total Time: 4:30

- Descent: 1,500′

- Distance: 6 mi

1 Comment